The Head-Turning Words

A title, one of many straightforward icons for a video game, captivates potential players from bustling market homepages by employing combinations of enchanting words. Unlike intriguing trailers with globally graspable soundtracks and graphics, the beauty of localized titles remains an enigma to outsiders, concealed behind language barriers, encrypted. Such an exclusive creation is tailored for local audiences who are connected by a common cultural root.

For contemporary players raised in a game-laden world and spoiled by recommendation algorithms, a purchase decision can be delayed easily in an attention-competing market. To take this notion a step further, it wouldn’t be inappropriate to assert that all video games of all genres are competitors to some degree for a gamer’s scarce concentration and time. A well-localized game title undoubtedly acts as a potent marketing fuel. It seizes fleeting opportunities to grab a gamer’s attention on their devices, and if lucky enough, the name per se may shift into a cohesive classic with the entire franchise, enduring for ages. As the phrase suggests, calling each thing by its rightful name, countless game translators have experimented with variegated approaches to title localization and evolved their techniques on occasion, but never strayed far from their primeval goal: titles cast aside all the fancy buzzwords such as ‘immersive’, ‘replayable’, and ‘true-to-life’ that are routinely abused on Steam pages while we aim to precisely deliver the developer’s idea to local audiences of interest with compact wordings, in one glimpse.

To ensure clarity, let me highlight that all the localized game titles mentioned here have their inherent purpose and were created in a particular situation. Controversial or not, they stand tall today, defining the product they labeled undeniably: via not only something in these names that can catch a gamer’s eyes while they scroll down in Featured & Recommended, but also the much more explicit ability to evoke immediate imagery in passersby, even when they are poring over reviews from competitor games and spot yours by chance. The definite appeal of a localized game title is not limited to the moment when native audiences are amazed by the bon mots within the name right off the bat; lest we forget, the very fact that even the most arguably incoherent title translations function as a gateway to local markets and are capable of stealing the spotlight on social media, also contributing to the game.

A Verbalized Motif

The frequency of fresh concepts in the video game industry springs to life like no other. Creators come up with innovative and occasionally rejuvenated, revised ideas every day and employ them in all possible forms.

Games are named at an early stage to deepen developers’ understanding of their own brainchildren. Even so, a title and the motif may update, sometimes drastically, as the developer progressively specifies the core idea. A canceled spinoff of Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time was as such. Inspired by the life of Hassan-i Sabbah and the feared reputation of Asasiyun society, this semi-fictional concept formulated by Patrice Désilets began to work under the title of Prince of Persia: Next-Gen during the first year as a transition attempt to take the Prince of Persia acrobatic gameplay and transplant it into an open world for the upcoming, then-unannounced next-gen consoles – the PS3 and Xbox 360. Having been approved by Ubisoft Paris, this initially prince-themed project was later named Prince of Persia: Assassins in preproduction documents, focusing on a young prince’s skillful bodyguards undertaking a story of protection and rescue. Two years later, the marketing team came up with another narrative-based name before GDC 2006, Assassin’s Creed.

A similar renaming story happened to the rogue-like action game Hades as well. In the early stages of development, the game was called Minos. Each run in an ever-shifting labyrinth was designed to reveal the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. Soon, Supergiant found out that retelling a conventional legend leaves little room for character remaking. What’s worse, the whole game appeared gloomy and tiresome because of Theseus himself. Creative director Greg Kasavin suggested changing the protagonist through and through; Zagreus had the stage almost immediately. Since Hades and his Underworld are not artist-favorite motifs in tradition, this fresh retelling features Zagreus as a rebellious son seeking to escape from an unloving father, but eventually connects all members of this big, dysfunctional family. The replacement of Theseus with Zagreus appealed to the team and facilitated a seamless integration of gameplay and narrative. Upon release, gamers raved about the idea of rewarding different boons from Greek gods through permadeath progress; their tittle-tattles against each other made each death meaningful and even enticing as a moment of rest in the loop. Surely, the to-the-point game title, Hades, hit the nail on the head.

Narrative rehaul often incurs title renaming. From the perspective of translators, although the games handed over to us are frequently unfledged and dynamic, especially for long-term ones, the game titles are often more lucid and ready to launch, accompanied by a meticulously designed artistic logo with even clever gameplay hints. However, just like how creators may change the motif, it is not uncommon to see translators make a change in the title localization.

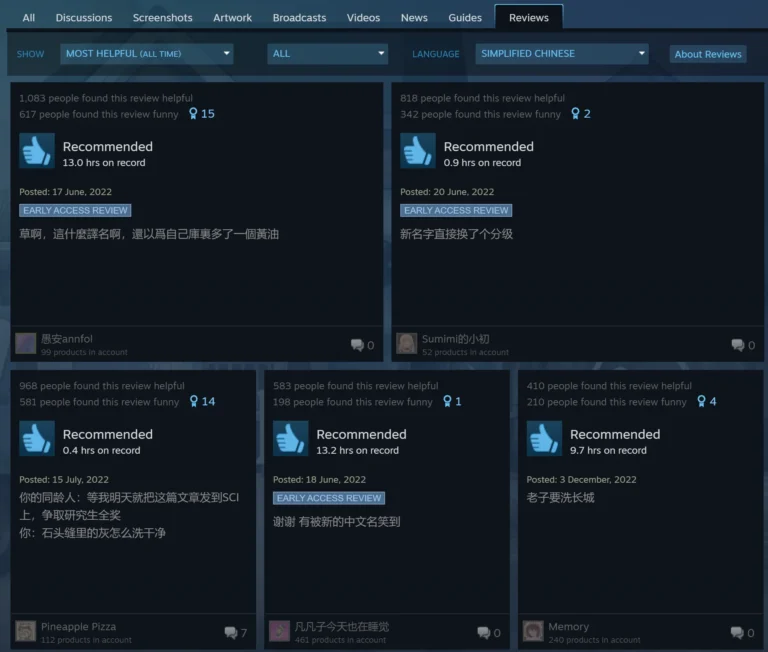

On 19 May 2021, FuturLab shipped its standout PowerWash Simulator, making it available in Early Access through Steam. As the refreshing name suggests, players manage a small power-washing business in the fictional town of Muckingham, and take cleaning jobs to fight against dirt in different locations in the form of levels. From buildings afflicted with graffiti, moss, and mold to an exploratory rover on Mars, players and their lan-party friends are provided with a range of washers, nozzles, cleaners, and extensions to jet highly pressurized water. While the word-for-word Chinese title from the get-go, 强力清洗模拟器, was lucid, FuturLab brought the full release of the game on 14 July 2022 and introduced another controversial yet entertaining localized name, 冲就完事模拟器, if you knew how to interpret it in another way. By applying an unorthodox double entendre, a game of shooting fun water now shifts to a polishing-your-rocket video game, imbuing a playful, nsfw innuendo. Predictable as much as it can be, the risqué wordplay does not appeal to everyone in the original player base. However, throwing cold water from sporadic critics failed to dampen the community’s enthusiasm: the market’s spike in Steam reviews in the same month proved that a creative, witty, even questionable, name is a force to be reckoned with. Even nowadays, the most valuable review in Simplified Chinese is a banter on this game’s amusing title. Such a twist between the title of pseudo-mature 17+ and the content of all-age was designed to deliberately mislead the potential customers with a humorous joke, and such a localization approach was handsomely rewarded by the native market.

Besides intentional wordcraft in video game titles, a proportion of game titles change due to the language’s inherent evolution. In popular culture media, language diffusion is often observed on the word choice level. Linguistic features spread outward from an originating, dominant center, but their influence weakens as they travel across greater distances and through longer periods.

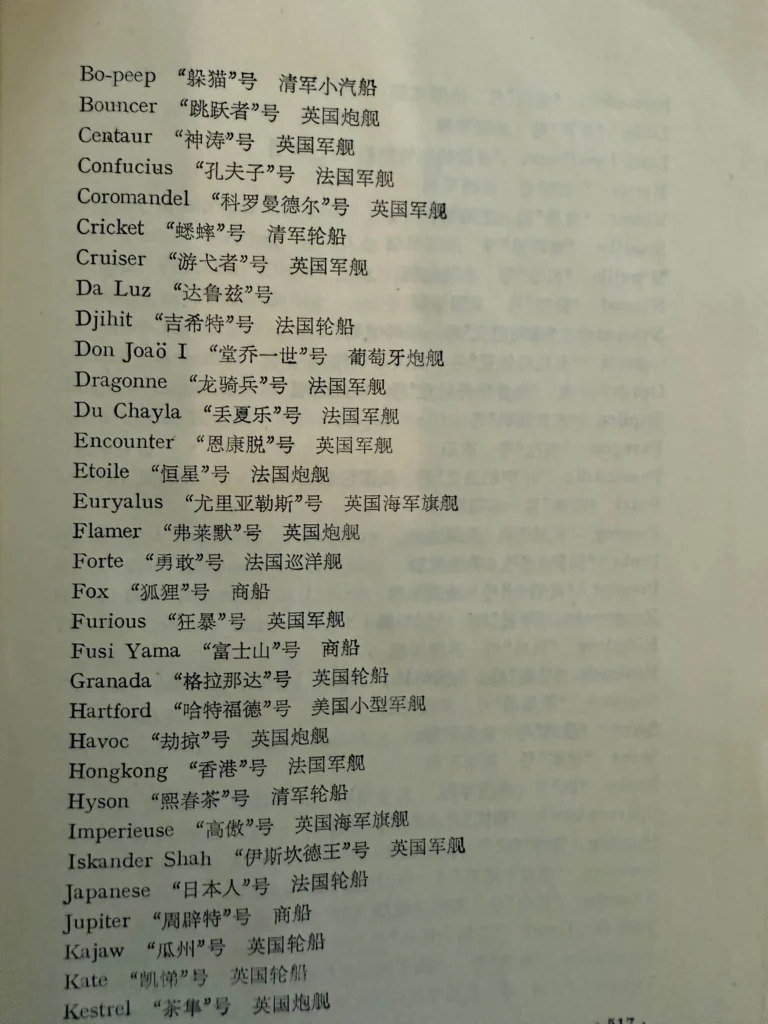

The term centaur is a perfect example of a translation discretion over contexts. First documented back in 麦都思英华字典 (p212, 1847-1848), the term was translated as 人马. However, during the Taiping Rebellion period, the UK’s Centaur warship adopted a phonetic name a la navy, 神涛号, ‘godly wave ship’. We can’t confirm the exact consideration behind this translation decision – maybe the locals still had little knowledge about European mythology in the 19th century, or the translator was a fan of phono-semantic matching. In the following two centuries of cultural communication, shifting from the outdated name 人马, ‘human horse’, to 人头马, ‘human-head horse’, eventually to the contemporary name 半人马, ‘half human horse’, this magnificent hybrid appears as a mighty stock character, beloved by artists, and now can be seen in many video games. The latter two translations are labeled on this mythical beast to a fault. Today, any title with this term can apply these go-to names without hesitation. The translation change, well, is left behind in history.

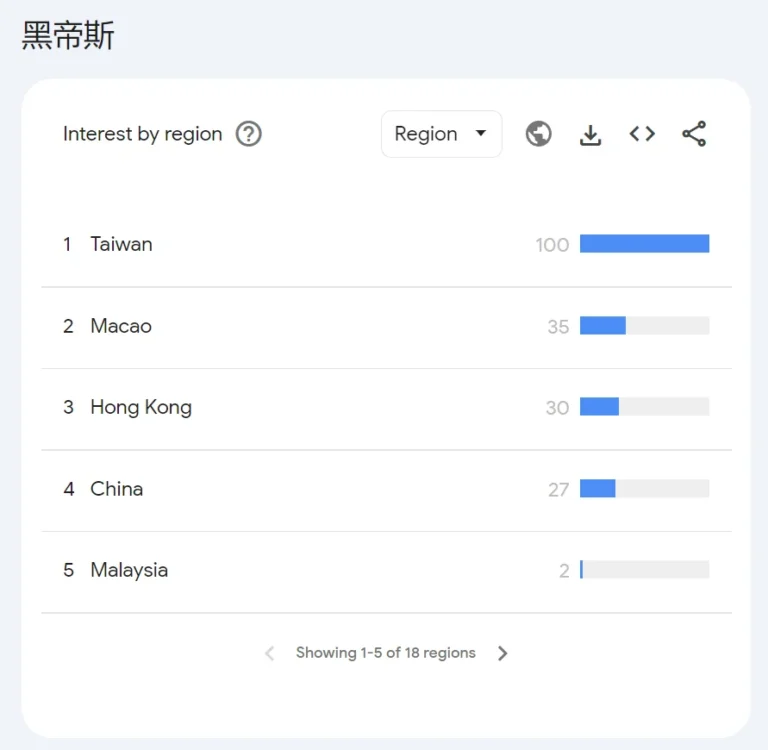

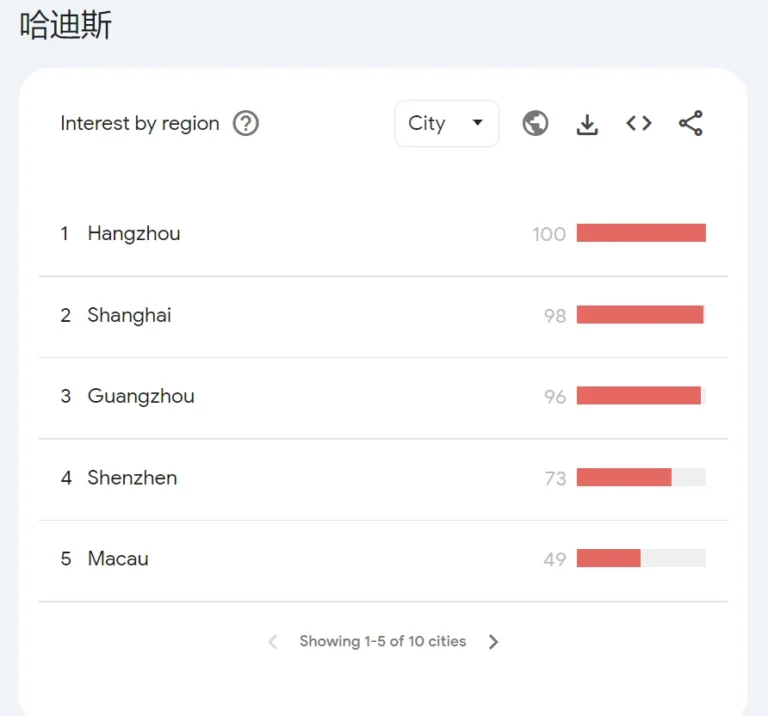

Hades, the eponymous title for the rogue-like dungeon crawler game, can be considered a geographic linguistic continuum example in translation. While contemporary names such as 哈帝斯, 哈德斯, 哀地斯, and 海地士 coexist, none of them can match the influence of the two dominant names, 哈迪斯, and 黑帝斯. China has preferred the name 哈迪斯 since the 80s: it is a time-stamped character populated by the most significant single contributor, Saint Seiya, representing the childhood fantasy of a time. When Supergiant localized their iconic Hades game into Simplified Chinese, 哈迪斯 was the original title issued through social media, however, the game changed the Chinese title to another version, 黑帝斯 later, which was not phonetically inaccurate, yet less customary in China and trendy in Taiwan, Macao, and Hong Kong. Though the new word choice emerged from the other end of the dialect chain, was understandable, and conveyed a daunting lord of darkness, the Simplified Chinese community often frowned upon the new name and insisted on the old-school choice. Worry not, the pique is temporary if the new name shows it was worth the trouble, as Hades is not and will never be the last game that adjusts its proper nouns.

Translate For A Bigger Picture

Knowing little about the game’s full vision narrows down a translator’s approach choices and may result in a word-for-word translation. The verbatim title style reads plain, but it’s a proven solution to stick to the entire motif in most cases, faithfully.

However, as the raw concepts and the full narrative that initially took shape as a ‘secret project’ churned within the minds of developers, the drawbacks of composing a premature title on the localization workers’ side were also obvious. Localizers, and sometimes along with artists, have less space to maneuver if the literal title and cover art become alive in the market when they have not seen the game’s bigger picture. The franchise story will also be shackled and left with little breathing room, with a title out of wild guesses. Even though the prototype may mark the most visible triumph in video game history because of its extraordinary content, seeing a sequel or two or even more, the long-term impact from an inaccurate title can not be dodged: for every finely-crafted product in the future, the community may spontaneously create another name for the franchise, and the momentum will keep going on.

The true meaning behind the name Far Cry remains debated. Some guess it is derived from CryEngine by Crytek, the original engine to power the game in 2004, while others bet on the narrative itself. Either way, Jack Carver’s rescue operation in a mysterious tropical archipelago features a far-cry-from-home story. Understandably, the first entry was translated as 孤岛惊魂, ‘(A) Thriller on Isolated Islands’. The game received multiple awards and became a commercial success at launch.

Fast-forward to 2006, after Ubisoft acquired all rights to the Far Cry series. Crafted by Ubisoft Montreal, Far Cry 2 flipped the script hard, featuring a significant change in the story background. Set in an unnamed fictional African nation in the middle of a civil war, the storyline made no connection to any island. The sequel premiered the change in environments and settings for this open-world franchise. Imagine how perplexed players can be when they are told to embark on a quest in the fictional Himalayan country of Kyrat, or to eliminate cultists in Hope County, Montana, while the Chinese title, Isolated Island Thriller, still appears as a clingy ex on cover art.

Fans in China, amused mostly, care very little about the mismatched Chinese name. Their volunteer word-to-word coinage, 远哭, is brilliantly dumb as a perfect meme gold for comment, banter, and a piece of fan art content. Although unofficial, its dorkiness outshines the authentic name in many ways. Maybe our island is in another title.

For better or worse, Far Cry is not the only video game with a strangely localized title. When Resident Evil, also known as Biohazard, was shipped in Taiwan, it came with the Traditional Chinese name 惡靈古堡, ‘Evil Spirit Ancient Castle’. It delights me to see another colleague use the rewriting technique, even if it’s controversial; a coded case to study their mind and translation strategy is simply irresistible.

Peter Newmark once defined translation as ‘the removal of reflections and ideas from the source language to the target language’. In practice, translators who employ free translations reproduce material without ordinances or content without its original form. In the debut of Biohazard, 1996, Chris Redfield and Jill Valentine must escape from a zombie-infested mansion. Is it really such a stretch to associate ‘mansion’ with ‘castle’? Maybe yes, maybe no. The only thing we know for sure is that, after the first hit, Resident Evil further expanded its storyline and maps. Mountains, forests, cities, islands, villages, prisons, industrial complexes, and what have you. Luckily for Capcom, the drawback of a specific location translation in the title didn’t limit the sequel escalation. After all, content is what gamers care about most.

Advocates in Taiwan argue that such a title rewriting actually grabs their attention in the retail section – spooky, vague, and inviting. Their neighbors across the strait are not so impressed, though. Even if it potentially nudges locals towards a purchase, critics in China bash the name for distorting the original’s survival-horror atmosphere, turning it into a supernatural B-movie. A perfect example of different strokes for different folks.

Capcom dodged the bullet, but not every developer shared their luck. Streets of Rage, an iconic beat’em up by Sega in the 90s, can relive the arcade childhood of any Chinese kids of my generation. Arcade games before 2000 were either barely translated or translated in poor quality by pirate manufacturers. They probably hired cheap amateurs in retrospect. Even though few teenagers could fully understand the scrolling narrative on the monitor, the eager young players still pieced together the gist and learned unofficial names from gaming magazines. That’s how the fan-translated name 格斗三人组, Fighters of Trio, spread and was attached to Streets of Rage initially.

Fans passed the catchy name by word of mouth. Soon, the second entry landed in 1992. Sega upgraded the sequel by adding more music, more moves, more levels, and above all, more characters. The unfortunate translator had to throw themselves under the bus, but still found there was no chance to undo what had been done. Clutching at straws, they eventually translated the new release as 格斗四人组, Fighters of Quartet.

Rest assured, the show went on. In 1994, Sega developed and published Streets of Rage 3 for Genesis. There were four available characters at the start, and by fulfilling certain conditions, players can unlock two hidden characters. SoR 3 had a more complex plot, inclusion of character dialogue, longer levels, more in-depth scenarios, and faster gameplay. But the old, mismatched translated title grew with the franchise as well. Now, should we call it Fighters of Quartet II or Fighters of Quartet III? It is said that the official name was set in stone this time. The inspiration came from an old cover art of SoR 2, featuring a tagline:

“懲りないワルに、怒りの拳を叩き込め!”

“Teach those incorrigible punks a lesson with your fists of rage!”

That marked the intricate birth of the name 怒之铁拳, Fist of Rage.

In 2020, Dotemu continued Sega’s Streets of Rage trilogy and published the fourth entry in the franchise. You guessed it – five playable characters this time. Up until now, names like Fighters of Quintet, Fighters of Trio IX, and Fighters of Quartet IX also survive among fans as a no-brainer. Even the game’s Steam page acknowledges their value and lists them altogether with the official trademark. The chaos is a legacy of an unsophisticated translation strategy. Entertaining as it might seem, it puzzles customers, especially for newcomers who know little about the history (also inviting curious souls to dive into the good old times). Leave some breathing room for a product’s long-term growth; that is what we need for a strategically localized name.

Overused Words In Titles

In 2024, I wrote an article and analyzed overused words in video game titles nowadays. The final result was straightforward. It won’t take much effort to realize that those mundane words are unlikely to appear in notable IPs. How so? A similar but far deeper article from Data Grand, written in Chinese, arrived at an insightful conclusion.

In their analysis, more than 540,000 ancient Chinese poems were sampled. After capturing information by obtaining vector representations of tokenized words with two trained models – Jiayan and Word2Vec, the author mapped multiple groups of set words from paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations. By transforming the word similarity calculation into a Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), the structured metadata was further tagged. Boring, right? The final take is much more captivating if it’s compared to the poems generated by GPT-2 (Generative Pre-trained Transformer 2). So, what’s the difference between a human wordcraft and a machine output?

The answer is stunningly simple and elegant. Allow me to quote the uncredited author(s) in Chinese:

从结果中,我们可以看到机器作诗时,红色和黄色的字概率分布区间占比较大,逐字生成时一般是从头部的字概率分布中来取,从而导致会诗句生成较为常见的表达;人创作诗歌时,各颜色代表的字概率分布区间占比较为接近,至少是差异不大,最终导致诗歌的表达千变万化,不落俗套。

古时诗人作诗,重在“炼字”。炼字,指锤炼词语,指诗人经过反复琢磨,从词汇宝库中挑选出最贴切、最精确、最形象生动的词语来描摹事物或表情达意。从这个角度来看,具有统计学意义的“选字”策略基本不可取 — 不是词不达意就是容易落“俗套”。

比如,陶渊明的那句“采菊东篱下,悠然见南山”中“见”换成“望”就不好。虽然按从诗歌数据集学到的概率来讲,“望”在过往出现的概率远大于“见”,但“见”通“”现,有“无意中看见”的含义,标明作者是不经意间抬起头来看见南山,表达了整个诗句中那种悠然自得的感触,好像在不经意间看到了山中美景,符合“山气日夕佳,飞鸟相与还”这种非常自然的、非常率真的意境,而“望”则显得有些生硬。

That’s the crux: when a trained model generates texts, the statistical regularity in repeated words is its forte and weakness at the same time. An AI’s training materials are from the corpus, known combinations. It generates an output sequence token by token, by predicting the most probable one in contexts. That’s why programmers introduce decoding strategies, like repetition penalties or sampling techniques, decreasing the likelihood of formulaic words. By contrast, human sentences are written with less repetition and a more diverse vocabulary, especially for a skillful wordsman. Savor those timeless Chinese poems. They strike hearts because of their selected, witty, and most importantly, unorthodox word choices to express the nuanced; those words are outlier data points in habitual linguistic patterns, pioneers who extend unclaimed definitions. That’s the secret ingredient of human creativity.

Back to video game title naming, what can we learn from this conclusion based on ancient Chinese poems? Simple: name and localize your game like writing a poem. Avoid clichés. Be creative. Challenge norms. Deliver wordplays. Embrace what has never been embraced before.

Make your game’s title, and the localized one, an outlier.

The Good, The Bad, And The Censored

Everyone has their worst enemy, including us language folks. Answers to this topic can be highly subjective, and mine is and will always be censorship.

Set in a futuristic, dystopian London, Watch Dogs: Legion features a story from a hacker syndicate’s POV, DedSec, which is framed by unknown culprits for a series of terrorist bombings. During their manhunt, DedSec also makes an effort to liberate London’s citizens from the all-seeing surveillance state, fighting against oppressive crime organizations. This is a proven narrative pattern ready for various tropes – wrongful accusation, La Résistance, Big Brother, and anti-heroes, you name it.

Naturally, recruiting random citizens to rise in defiance of their oppressors was designed as the core gameplay. Even more naturally, localization workers for Traditional Chinese captured the motif of liberty and seasoned it with a pinch of call-to-action flair in the title, delivering the name 看門狗:自由軍團, which means Watch Dogs: Liberty Legion, and shipped the game in Hong Kong and Taiwan. On the other side, the Simplified Chinese version displayed more faithful wording in form 看门狗:军团, omitting the keyword ‘Liberty’.

Linguists have proposed numerous translation theories in history. It’s not difficult to find academic reasons to support both addition and reduction as practical translation approaches, equally accepted by professional localizers. Watch Dogs: Legion, however, was unfortunately mired in criticism due to a series of sensitive moves in a turbulent time. In 2019, tensions mounted in Hong Kong over a controversial extradition bill. Escalating protests, police inaction, and brutality further plunged the tolerance of the public toward the government, while the apparatchiks were also losing patience.

When Ubisoft dropped a Watch Dogs: Legion ad in June 2019, the high noon when everyone stared each other down, featuring masked figures who also held umbrellas in a sea of others with umbrellas, the imagery evidently evoked a reminder of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement five years ago. The déjà vu, implying support for protestors, nuked an unprecedented backlash. Despite Ubisoft issuing an apology and deleting the original post later, claiming the game was apolitical as a fictional artwork, the factual removal of Liberty in the localized title, surely, doth protest too much.

Omissions for certain words in a title can be interpreted from a range of angles. Perhaps only the decision maker in Ubisoft’s high chair knows why the title lacks Liberty in China. Whether true or false, Ubisoft apparently regarded the title localization as a part of the content guidelines. But not every developer is a fan of compliance; what’s more, they beat censorship at its own game by abusing the disallowed as a marketing tool.

Ratchet & Clank by Insomniac Games is one of a kind. Who would have thought a cartoon-like adventure shooter, generally rated E10+ by the ESRB, would be kinky in suggestive wordplays that brazenly defy their kid-friendly ratings? Several titles hint at an nsfw joke or pun. Going Commando, Up Your Arsenal, Size Matters, Quest for Booty, and Full-Frontal Assault are blunt legacies we can still find in the marketplace today. Each of them is an intellectual challenge for localizers who want to strike a balance between logopoeia and regulations.

More abandoned titles were known through interviews with their content creators. A Crack in Time was nearly Clock Blockers, and All 4 One considered 4-Play, later used as its Platinum trophy. Into the Nexus kept the pun alive with a trophy, Into the Nether Region.

Fans were entertained, but organizations that assign age and content ratings were not. Some of the games had to comply with the local regulations and water down the edgy sense of humor during localization. For example, Up Your Arsenal was localized as Ratchet & Clank 3 in Europe and Japan, but Australia kept the original title. The discrepancy caused by regional censorship serves players a hilarious topic, spawning countless memes, title tier lists, and discussions about localization differences across gaming forums. As expected, fan content mingled with the franchise as a part of the game’s cheeky reputation and appeal.

The intentional innuendo works as a customer filter. By employing the playful style in titles, the R&C series takes less effort to target its audience, often considered to be late teenagers and adults rather than kids. Such a player base is more engaging, more active, or at least not easily offended by an inappropriate phrasing. Those who are sold soon find out the content itself is even more risqué and comic than the titles. Everyone enjoys this cat-and-mouse mind game, except for rating guys, methinks.

Communis Error Facit Jus

Two wrongs don’t make a right, but a thousand can overwhelm. That’s why it’s pivotal to nip the first wrongdoing in the bud. Unattended errors sprawl and entwine, slowly encroaching upon the mass.

Every Chinese kid my age shares a heartwarming nostalgia: in that languid summer afternoon, huddling around the TV with friends, we plop down on the living room floor, and have a blast on Super Mario Bros till our parents nag us for playing too long. But no one can play too long, especially with the jumpy plumber with a beautiful mustache.

Mario is one of the most iconic characters in video game history. In the 80s, the game Super Mario Bros was widely known in China as 超级玛丽, a name printed on unauthorized cartridges with the pixel protagonist. As a simplified phonetic adaptation, the name 玛丽 omitted the ‘o’ sound, making it more friendly to natives. Dealers selling unlicensed ROMs – street vendors, electronics shops, or importers – quickly noticed its popularity. The game was bundled on mass-produced bootlegs in underground factories as a standard-issued game, flooding pre-WTO China.

Amid lax copyright enforcement, the whole supply chain was rooted in piracy. Even though Nintendo established anti-piracy teams by the late 1980s, filing lawsuits worldwide, their delayed interference in China allowed the black market to thrive. From 1990 to 2000, a variant name 超级马里奥 emerged, closer to its English source in full phonetic sound. This update later bridged the early translation and the eventual registration in China, nuanced in subtle tones.

Another barrier that hampered Nintendo was the console ban (2000-2014) imposed by China government, which legally created a long vacuum. While foreign-owned enterprises were blocked at the gate, copycats branded original designs as ‘domestic’ consoles more easily. But Nintendo didn’t cease its efforts to combat rampant piracy and penetrate the biggest Asian market. In 2003, the official name 马力欧 debuted in iQue’s flagship product, the iQue Player, with multiple Mario-inspired games. As a joint venture circumventing the console ban, iQue released a series of China-exclusive hardware and software releases, marking Nintendo’s official entry into China. The new name 马力欧 mirrors the Japanese sound, with 力 adding a deliberately childlike flair of strength, making the character livelier and more approachable.

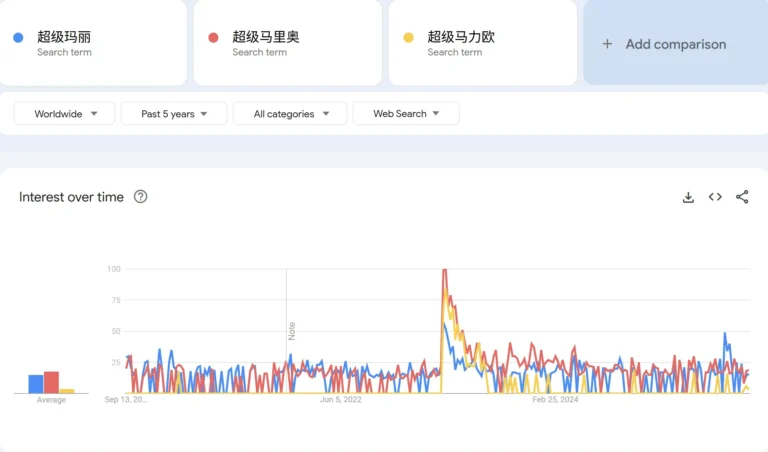

While our Italian uncle has a registered name now, the old prototypes coexist. But what is the community reaction to these three names? Google Trends shows that in the past five years, the full-sound adaptation 超级马里奥 won the most interest, followed by the earliest name 超级玛丽. It fits my personal experience, too. Among Chinese gaming forums, the transitional version 马里奥 appears to dominate in player parlance, repeatedly mentioned in posts, comment threads, videos, shorts, or daily conversations. It is a nostalgia beacon that no one can outshine. Despite Nintendo ramping up efforts to popularize the new name 马力欧, often criticized as too formal, its acceptance still can’t match the precedent versions, even the crass, meme-worthy 玛丽. During Nintendo’s absence, the first two names helped build brand awareness. On an individual level, those piracy names, knowingly unofficial, are still etched in our minds.

Super Mario Bros was not the only copyrighted game sourced by bootleggers in China. Another infringement, however, was associated with a much more entangled IP mess across the world, leaving zero chance to undo the then-localized name.

Tetris, another trigger word for childhood, first trickled into China around the late 80s. While Nintendo’s glossy Game Boy and Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) were both licensed with Tetris and achieved commercial success worldwide, the original hardware was prohibitively expensive for ordinary Chinese families. So, what did we do? Piracy. Sorry again, Nintendo.

Digital smugglers crammed dozens of games into one cartridge as a compilation to hook buyers. Bundled alongside many classic games, Tetris still stood out as a star attraction. The bewitching simplicity needed no tutorial; even the sternest Asian dad I know was attracted by the blocky game. Unlike Super Mario Bros, Tetris didn’t and still doesn’t have any Chinese name variants. The name 俄罗斯方块, ‘Russian Blocks’, was a legacy from the infamous period, translated by an unknown pirate.

Why Russian Blocks? You might ask. Today, the Chinese internet rumors that it was a nod to the Russian origin of its developer, Alexey Pajitnov. The guess is unlikely to be convincing if you think twice. In pre-Internet China, pirate manufacturers had little chance or interest to learn a developer’s life path or anecdotes. Even hearsay had no channel to spread. Early Tetris versions featured a castle with onion domes in gold, green, blue, and red in the title screen. After clearing a level, four characters in traditional garb would appear from each side, cutting a rug in a Slavic folk style. In some versions, the castle would join the celebration by skyrocketing fireworks. During the gameplay, the Moscow-style aura was reinforced by the theme tune, a remixed Russian folk song known as Korobeiniki. The entire game oozed Eastern European charm and presented itself as 俄罗斯方块.

As Guinness World Records claimed, there were over 220 official versions of Tetris across more than 70 platforms by 2023. It is impossible to identify the exact Tetris versions traded in China then, not to mention the copyright war around the Tetris trademark didn’t cease until the licensing rights ultimately reverted to Pajitnov in 1996. In its official attempt to reclaim its rightful influence in China, The Tetris Company co-developed Tetris-branded games with a Beijing-based studio in 2018. Over the following years, the media announced a few licensed games under the company’s belt, while the old, de facto Chinese name was also kept in marketing content. At least from public reports, The Tetris Company doesn’t have the intention to challenge the common currency.

The era of errors is behind us now, while the tarred trademarks still have to live with unauthorized names. Only a few behemoths can defend themselves or even fight back for their stolen claims. For most developers, one oversight in title localization may permanently damage the growing franchise. Those unintended yet influential coinages are vulnerable weak points in legal, and a reminder of after-the-fact enforcement in history.

Better Call Local Counsel

The fascinating history of game title localization is a tapestry woven not only from creative genius but also from the legal skirmishes fought over a few well-placed words. The power within words, in a drop of cultural consensus, is true magic in real life – a force so enticing that everyone wants to wield the pen.

In practice, even communities sharing one cultural root may branch apart in localization. Since its debut in 1996, the Pokémon series has been translated as 寵物小精靈 in Hong Kong and 神奇寶貝 in Taiwan. In the 1990s, when China’s television stations began importing anime from both, it created a linguistic patchwork quilt of names. This gave rise to the 宠物小精灵 and 神奇宝贝 titles coexisting in the mainland, cementing Pokémon as a byword for a generation’s childhood across the Sinosphere.

This chaos was a snake pit. The China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) database shows that individuals and entities started trying to stake their claims on key localized Pokémon names as early as 1998. Those trademark hoarders, however, challenged the wrong opponent. Nintendo’s legal team, often jokingly dubbed by Chinese fans as ‘the Orient’s Mightiest’, filed oppositions to thwart IP thefts. Leaving no stone unturned, their applications locked down all key regional names. While many battles were won swiftly, the full-scale brand unification to 精灵宝可梦 was a different beast altogether, not finalized until 2016. The most infamous case, involving a mobile game called 口袋妖怪复刻, was a full-blown trademark infringement lawsuit that Nintendo and its partners fought and won much later, in a stunning victory that awarded them a record-breaking settlement.

Escorted by its legal cavalry, Nintendo’s journey to safeguard its creations is a walk in the park. Shueisha, on the other hand, had to fight an uphill battle when co-publishing One Piece video games in China.

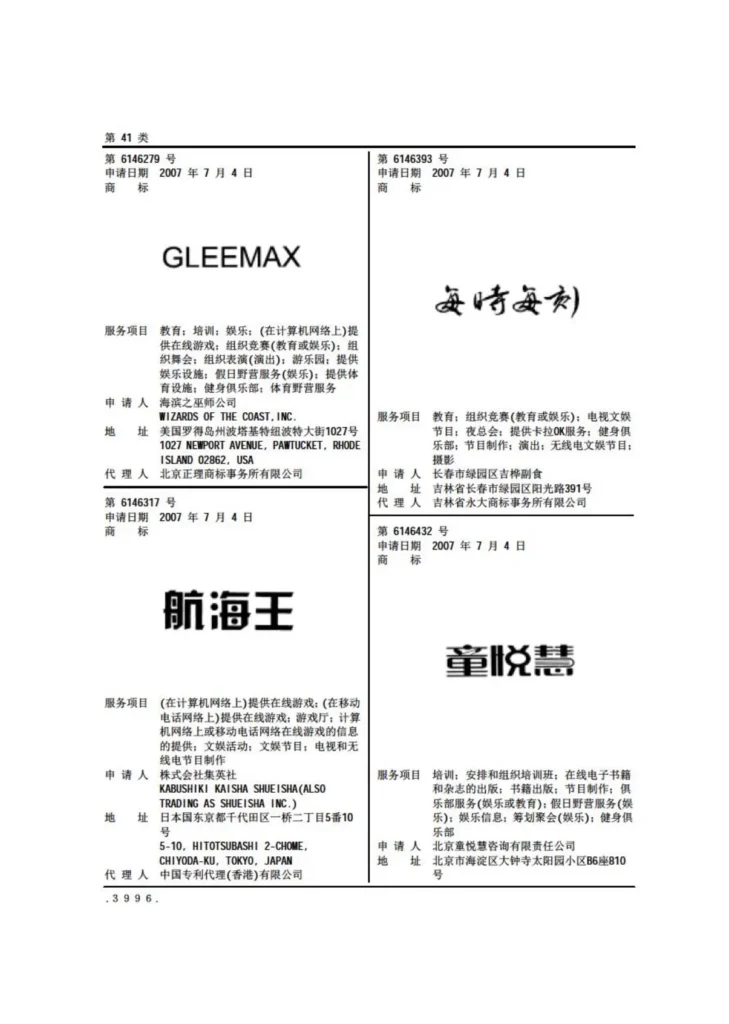

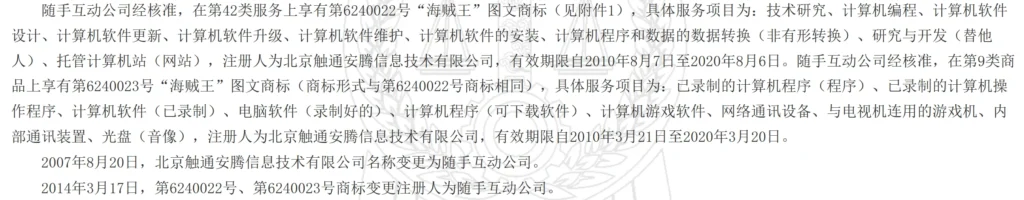

As one of the world’s most influential intellectual properties, One Piece’s entry into China was met with immediate challenges. Arriving via bootleg VHS in the early 2000s, it quickly gained a vivid, localized name, 海贼王, ‘Pirate King’, that had a ring to it. In July 2007, Shueisha applied for a Chinese trademark 航海王, ‘Navigator King’ to align with Taiwan/HK licensing. However, they missed a beat, failing to secure the classic 海贼王.

In what seemed more than a mere coincidence, just one month later, in August 2007, a Beijing-based entity called Troodon Entertainment Technology Ltd. (北京触通安腾) filed for the 海贼王 trademark. That same month, the studio rebranded itself as 随手互动 (Suishou Interactive). In March 2010, the Pirate King trademark was approved under NICE Classes 9 and 42—two months before Shueisha’s Navigator King received approval in May 2010. The most beloved name had slipped through the IP holder’s fingers. The precise timing mentioned by multiple public resources brought up many questions. Was Troodon actively monitoring the trademark application process and/or the official IP licensing news related to One Piece? Was it an internal leak from Shueisha? Why was a later application approved two months earlier than a preceding one after three years? We can never know. But what we do know is that Shueisha’s 2013 legal challenge to reclaim 海贼王 proved futile, rejected due to Troodon’s squatting. Following the legal battles, the stolen trademark was transferred from Troodon to Suishou in 2014, officially consolidating under the renamed entity.

Fans have spoken. They prefer the classic memory trigger rather than a dry alternative. However, Shueisha’s subsequent games in China were forced to stick to 航海王, a bitter pill to swallow for fans and rights holders alike. As for the Troodon-turned-Suishou squatter, it exploited the trademark and lost a court case against two Chinese trademark thieves who also attempted to hitch a ride on One Piece’s reputation. But that’s another story too long to tell here.

One reason behind China’s unbridled bad-faith registrations is its first-to-file system. Unlike first-to-use countries, including the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and the UAE, where prior use can be used to defeat a later filing, China generally operates in a by-book mode, albeit with growing flexibility, in branding protection.

Chinese law recognizes exceptions for well-known marks and bad-faith registrations, as seen in disputes regarding Fruit Ninja, a mobile game by Halfbrick. Fruit Ninja was named one of Time magazine’s 50 Best iPhone Apps of 2011 and reached 1 billion downloads in 2015. Besides its verbatim name 水果忍者, it earned another shortcut nickname 切西瓜 in China, Slice Watermelon, due to its app icon. In 2016, a Chinese individual filed 17 trademark applications for a resemblance concept, 西瓜忍者, Watermelon Ninja, in a selection of classes, including texts and a watermelon logo. Since 2017, Halfbrick has lodged invalidation requests along with various pieces of evidence. CNIPA recognized the game title’s value and impact through the following filings; moreover, the individual was confirmed as a malicious hoarder for unnecessarily covering multiple registrations regarding several celebrities and Oculus’s localized name in China. Her registrations were later invalidated.

Rights holders may seek assistance from the WIPO Madrid System, a procedural convenience for filing a single international trademark application in multiple countries. This system streamlines the process; however, it does not guarantee a smooth ride in all jurisdictions. Trademark offices in member countries still get to review as per local laws. Supercell’s hit, Clash of Clans 部落冲突, learned this the hard way. In 2012, the year of the game’s launch, Supercell attempted to extend its territorial protection to China in class 41 through the Madrid System. The application was reportedly met with a provisional refusal in 2015 due to issues like potential ‘kinship clan’, 宗族, interpretation, and conflicts with prior marks. This partial rejection demonstrates that while the Madrid System provides a one-stop filing solution, it is not a silver bullet to bypass a country’s domestic laws. In the end, the Finland-based studio only secured its turf in two core gaming classes, 9 & 28.

Though once a magnet for opportunists, China’s first-to-file system has become more pragmatic. In 2019, the Trademark Law Amendment was enacted, identifying bad-faith filings as illegal and providing grounds to protect rightful owners. The new day dawns; through strategic legal actions, developers can now reclaim and defend their localized intellectual property in a marketplace once ruled by chaos.

For language service providers, a precautionary practice to support customers is to consult the local IP administration’s database before localizing the video game’s title if the target language bridges to a first-to-file jurisdiction, such as China, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Russia, Indonesia, Brazil, most EU member states, etc. Notably, a video game falls into classes 9, 28, 41, and 42, depending on its form, according to the Nice Classification, the international system used by WIPO and most IP systems. Visual and phonological similarities between trademarks also need to be taken into account.

But as the ultimate resort for detailed aid, I bet you already know. Better call local counsel.

Approaches Of Note

Compared to the intricate title localization history, title localization is simpler, shimmering with pure linguistic finesse. Localization passes information via one compressed code from multiple layers, conveying the game’s niche, appeal, and purpose. The art of wordcraft has been analyzed by linguists with all sorts of theories. The modern-day translators, while acknowledging their academic contributions, still seek new possibilities where visual, phonetic, and semantic intention can unite. Their techniques are worth noting, too.

WORD-FOR-WORD

As Peter Newmark argued, “Translation is concerned with moral and factual truth. This truth can be effectively rendered only if it is grasped by the reader, and that is the purpose and the end of translation. Should it be grasped readily, or only after some effort? That is a problem of means and occasions”. Text ranks of importance reign over the choice of translation means. And for the title, the most important text for any video game, is often closely translated to its source format due to its unique occasion. Word-for-word, as one of the most faithful translation approaches, leaves enough potential for franchise growth and grants players easy access to the game’s intention, while it is often criticized for introducing an unidiomatic translation form, even lacking logopoeia (pure meaning within a group of words). Word-for-word translations, when defying the TL’s syntax, don’t stimulate the visual imagination with phanopoeia (visual imagery created by words) or induce emotional correlations with melopoeia (sounds and rhythm of words). This innovative combination from an outgroup creation, however, can be seen as a marketing ploy to attract local customers.

Games with a strong exotic atmosphere can also be seen employing word-for-word localization in their title. It preserves the original flair to the greatest extent, at the cost of interior accessibility to locals. For an opaque name, it takes proper art style, a brilliant theme tune, and a good teaser altogether to invite customers.

Sometimes, when the title source is plain in phrasing, the verbatim localization leads to a counterpart lacking distinctiveness. Multiple cases worldwide demonstrate that the absence of distinctiveness in titles can lead to brand refusal in the IP system. The Czech studio SCS Software s.r.o. was rejected by the European Union Intellectual Property Office for this when registering its creation, Euro Truck Simulator, which was later approved with various pieces of evidence. Similar rejection reasons were presented in both trademark cases of Modern Warfare ‘现代战争’ and 倩女幽魂ONLINE, a namesake from a vintage movie, in China. While those title disputes were caused by the ubiquitous word choices in the source rather than localization, localizers still must be aware of potential legal risks when applying the word-for-word approach if the initial title lacks creativity.

SYNONYMY

As a type of free translation technique, synonymy is criticized by linguists for its ‘simple attempt at sameness replacement’ in words. Some of them disapprove of synonymy as a translation. Peter Newmark claims, “I do not approve of the proposition that translation is a form of synonymy”. Susan Bassnett-McGuire takes a step further in detail, “hence a dictionary of so-called synonyms may give the word perfect as a synonym for ideal or vehicle as a synonym for conveyance but in neither case can there be said to be complete equivalence, since each unit contains within itself a set of non-translatable associations and connotations”. However, from the perspective of a man who sells his words, I acknowledge the marketing preference towards synonymy in title localization nowadays. For a video game, while it does associate with artwork attributes, it is also a commercial product integrated with multiple elements. If the community regards synonymy as a good localization approach, then it must be for some overlooked factors.

In practice, synonymy maintains the surface structure of phrasing and focuses on replacing the SL terms with synonyms, eventually reaching another expressible idea in the text’s deeper structure. Worldwalker Games LLC’s game Wildermyth is such an example. The Chinese title 漫野奇谭 keeps the constituents in the compound, using synonyms that any dictionary would suggest. To break down the name further, here are a few meaningful candidates to select from.

For the word ‘wild(er)’, as in areas:

- 自然地区, ‘natural areas’, neutral, often seen in formal contexts such as media, reports, etc, highlighting the intactness and primitive natural environment.

- 偏远地区, ‘remote areas’, neutral, often seen in formal contexts as above, highlighting its outlying characteristic. This phrase can also be a euphemism for a poor economy, peripheral cultural influence, and subdevelopment.

- 荒野, ‘wild barren’, neutral, often seen in casual or literary content such as poetry, prose, etc, highlighting its desolation, lifelessness, and inability to produce.

- 荒地, ‘wild land’, neutral, often seen in formal contexts, blurring the size. It can be used on a large area or an abandoned patch.

For the word ‘myth’:

- 神话, ‘myth’, neutral, often used as a genre of folklore involving natural or supernatural in character.

- 传说, ‘legend’, neutral or occasionally positive, often used as a genre of folklore involving human characters, especially as the main character; by extension, it can be used to praise someone for their feats.

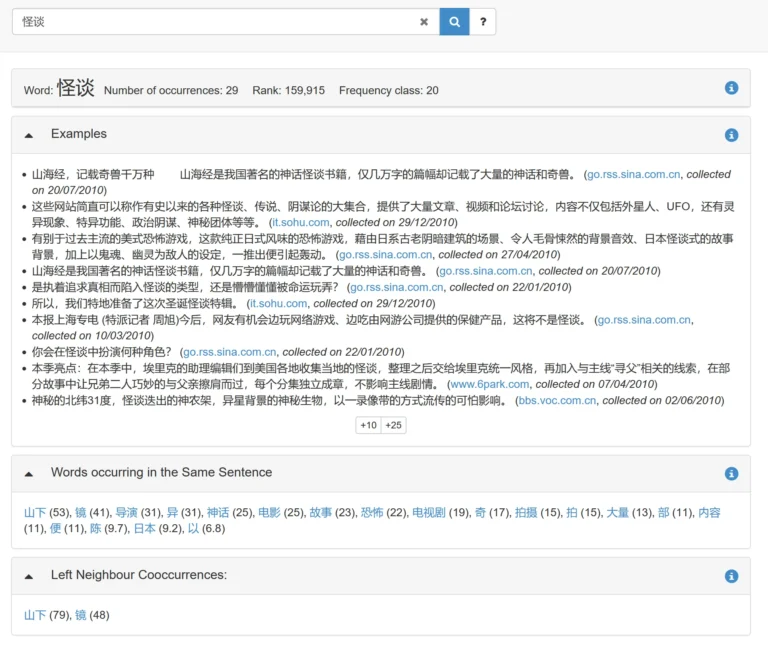

- 怪谈, ‘strange tales, often about ghosts’, neutral, a loanword from Japan for a genre of thriller content involving supernatural elements.

- 轶闻, ‘unpublished tales’, neutral, often used on tales that haven’t been proved, hinting at the questionable authenticity, and mostly used in casual contexts.

While the candidate words above have close relations to key constituents, they are nuanced in subtle preferences in register, tone, genre, denotation, and connotation. They fall into habitual patterns, and natives unknowingly expect neighbor cooccurrence (words that occur noticeably often together with a sample word) with any given one because of the large amount of text that already exists in modern corpora. For example, if myth (3) is applied, words like ‘都市/urban’, ‘异/strange’, ‘恐怖/horror’, or ‘日本/Japan’ show significant relevance; the text style can easily shift to a typical Japanese scary movie if the creator injects relevant elements via other forms, e.g., art, music, character, narrative, etc. For each word, its inbuilt syntax usage and semantic relations with other words are almost fixed, conveying an irreplaceable vibe in texts.

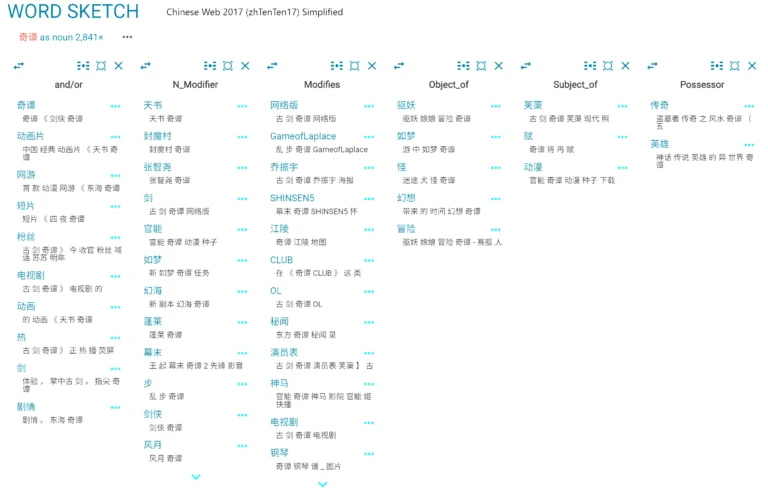

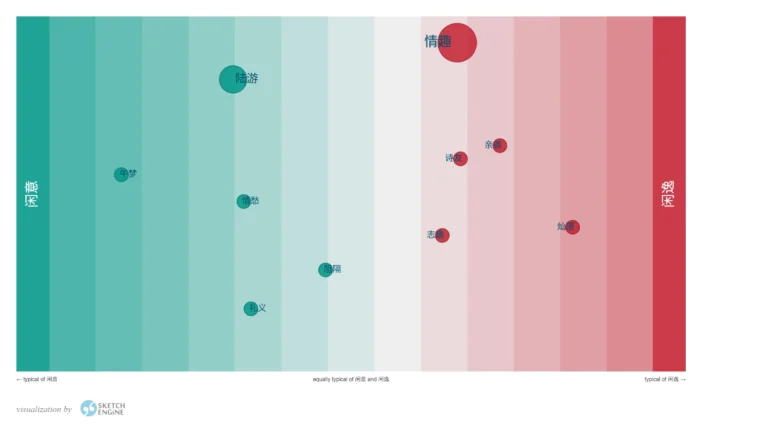

Localizers should be aware of the fact that synonymy isn’t just about dictionary equivalence—actually, there is no such thing as complete synonymy (Said Shiyab). Synonymy is about managing entire semantic networks and cultural associations. Hence, it’s understandable that Widermyth, with its eye-catching 2D papercraft diorama and a pop-up storybook art intention, eventually chose other synonyms carrying heavier poetic aesthetics to substitute for SL terms. The name reaches a deeper layer of visual expression and narrative-driven fantasy story, as shown below by sampling 奇谭 as an example. A truly brilliant strategy.

Another example of a synonymy localization is Little Chef: Cozy Cooking by Julien Truebiger, Hello Erika, and Danny van Duist. The Chinese name 小小厨师:闲意巧炊 features multiple replacements of the original English words, yet by gently steering toward a family-friendly, poetic aesthetic, the name subtly reveals its joyful puzzle gameplay. Unlike word-for-word, synonymy drifts from SL terms based on a localizer’s perception. Their intention, interpretation, and navigation of semantic networks determine what additional information emerges.

For example, the visualization below shows the current translation, 闲意, for the word ‘cozy’ and another synonymous candidate, 闲逸, feature different collocation (a sequence or combination of words that often occur together) preferences in Chinese Web 2017 (zhTenTen17). By identifying co-occurrence in the corpus, the current word choice 闲意, as an object, shows a weaker poetic relation than 闲逸. While the quantified data may tell us a simplified collocation result between these two words, the final decision is made by a localizer’s subjective cognition, depending on their expertise, experience, and knowledge base. For a casual game like Little Chef, how much poetic flair is acceptable, and how much is too much that might drag the reading resonance to a fancy poem? That’s something to be cautious with.

Besides the pure linguistic factors, external constraints such as current marketing competitors, client directives, and especially counter-arguments from other localizers in the team may also affect how synonymy works. Each individual has their own taste for semantic relations for words. A title of synonymy proposed by the translator might be shot down by the reviewer, the agency, the developer, and/or the publisher. Yes, teamwork makes dreamwork, but synonym selection can become contentious when team members’ linguistic intuitions clash.

TRANSFERENCE

The closest translation is transference, where the source language (SL) or idiom or collocation or cultural or institutional term is already more or less rooted in the target language (TL), provided the term has not yet changed its meaning. Transference is one reason behind converted idioms in the local corpus, such as 武装到牙齿 (lit. armed to the teeth) in Chinese, or ‘long time no see’ (lit. 好久不见) in English. Transference-based titles are close to the source texts to a fault, connoting a less familiar image to natives, even though they are grammatically or lexically comprehensible. In practice, this approach can be shot down by reviewers since it defies habitual combination in TL, which is regarded as a mistranslation if differences in frequency, usage, connotations, and lexical gaps in other languages haven’t been acknowledged by the majority.

To Chinese gamers, transference-based titles can often be found in titles phrased by another Sinosphere syntax, albeit with exceptions. Cultural similarity facilitates the transfer of neighboring concepts more easily. The process of transference is a form of source-text-oriented means, preferred by sourcier (Jean-René Ladmiral) translators. As seen in the example of サムライスピリッツ/Samurai Spirits, a fighting game series by SNK, Chinese teens in the 90s demonstrated high acceptance of its original kanji title 侍魂. Take Stigmatized Property by Chilla’s Art, another example. By importing its kanji name 事故物件 to the Steam Chinese page directly, the game requires zero brainwork in title localization. The emphasis in transference lies in historical and socio-cultural influence, as this approach is a relatively risky means relying on a continuous, concrete language heritage.

However, when the influence of a geographically distant term becomes a juggernaut in popular culture, the title localization choice shifts smoothly to transference. Cyberpunk 2077 is such a case. The word ‘Cyberpunk’ undeniably defines a literary genre from the science fiction realm, and that, for a game, it also indicates the type of game, i.e., a cyber-inspiring game. The global consensus waives further introduction for this concept; hence, its Chinese localization simply applied the known phonetic-transcription name 赛博朋克2077.

TRANSCREATION

Transcreation, among all the approaches, is the only one abused in many LSPs’ marketing pages. The question is, to what extent can a translation work be called transcreation? Is pure violation in syntax sufficient, or does it also require reforms or even fusion in phonetic or semantic to be qualified? The definition’s ambiguity leaves a large blank for this approach.

Transcreation must be processed by a degree of other loose translation approaches with low closeness, such as paraphrase, synonymy, cultural/functional equivalent, etc, featuring the distinctive untraceability in back-translation. The final work is a blatant rewriting as creative treason (Robert Escarpit) that is greatly different from the original texts. Localizers who deliver transcreation first have to use low-closeness translation techniques, turning their backs on the original content’s form by composing new materials, before introducing an aesthetic equivalence in loss, at the layers of phonetic, semantic, visual, linguistic, cultural, functional, etc.

The best example is Evil Wizard by Rubber Duck Games, a humor-filled action RPG shipped in 2023. Its Chinese name cracks a smile for any native who ever saw it – 祖上阔过的二代坏蛋巫师反击伪善英雄夺回祖传城堡的神奇大冒险. The audacious rephrasing perfectly fits the game’s entertaining idea by brazenly stuffing the protagonist’s profile, narrative, and predicament into one verbose sentence, as a title. Yes, its literal translation is: The Amazing Grand Adventure of a Second-Generation Villain Wizard from a Once-Wealthy Family Fighting Back Against Hypocritical Heroes to Reclaim His Ancestral Castle. I bet the smile is even on a non-native’s face now. Such a goofy localization compensates for the plain source title, serving as a loquacious one-liner to amuse passersby.

Transcreation is based on free translation while introducing new information in TL texts, occasionally at the cost of erasing the source information. The density, form, and accessibility for a creative touch vary over the genre, theme, niche, purpose, and even regional censorship. In many cases, new information is extracted from the game content itself, e.g., Far Cry, 孤岛惊魂 ‘(A) Thriller on Isolated Islands’, Red Dead Redemption/荒野大镖客 ‘Wildness Big Guards’, or Tomb Raider/古墓丽影 ‘Ancient Tomb Pretty Woman’. This tactic balances the aesthetic needs, translation fidelity, and the game’s intention.

Sometimes transcreation can be a wordplay engineered on known idioms, proverbs, memes, norms, or even other popular culture content, either for a tribute or a parody. For example, Dead Pixel Tales’ cozy and soothing puzzle game Stick to the Plan/过木不汪 ‘Pass (the) Wood No Woof’ is a clever homophonic tweak from a Chinese idiom 过目不忘 ‘to have a photographic memory’. Understandably, this is a common angle to transcreate a title when a game launches a new franchise and has no similar publications to impress customers. Localizers naturally employ rewritings over existing linguistic assets.

When a video game’s title can hitch another artwork’s reputation, transcreation, despite being potentially seen as a refusal to exert effort in this case, can be quite easy. Ken Follett’s The Pillars of the Earth/圣殿春秋 ‘Temple Spring and Autumn (as in time)’ borrows the homonymous tale’s established name, similar to Cat Quest/猫咪斗恶龙 ‘Kitten vs Bad Dragon’, mimicking the Chinese title for Dragon Quest/勇者斗恶龙 franchise, ‘Adventurer vs Bad Dragon’. Are translations leveraging reference materials transcreations? Maybe. Should creativity always be wholly innovative? You hesitated. Can we even create anything from voidness? Ha, gotcha. Titles like these do blur some lines, yet they gain more in marketing. True it is that a borrowed [re]name acts as an instant, high-level descriptor. An ‘insider’s wink’, if you will. These opportunistic creations immediately feel familiar and trustworthy to the local audience and will reduce the psychological barrier to purchase.

SOUND-BASED

Transliteration, the conversion approximates the sounds of foreign words by using the characters of the native language’s script, seems to be a relatively rare approach in Chinese-targeted translations, especially in video game titles. Chinese exhibits high morphological transparency in both root words and compounds, given its logogram writing system, lacks grammatical inflections in words, and has an oracle-rooted pictograph hanzi system. A ton of Chinese words favor a meaning-oriented feature, and have a self-explanatory coinage logic in form. While we do have words labeled as 联绵词/disyllabic morpheme, a word-like morpheme that actually cannot be divided into meaningful units of the inferior level, hanzi, in Chinese, they are still a minority compared to the vast number of compound words in the entire lexicon. Such a unique trait in the Chinese naming convention encourages native translators to apply approaches that value inner meaning rather than the ostensible phonetic traits.

But never say never. Transliteration still has its place when adapting names of non-Sinosphere figures, locations, and concepts that haven’t bridged to a semantic translation. Hence, it’s understandable to see the speedy hedgehog franchise translated to 索尼克 based on its sound as a figure, Terraria, a dream land, named as 泰拉瑞亚, and Cyberpunk popularized by the name 赛博朋克.

Chinese transliteration is deeply influenced by sound symbolism. Here is an example in plain English: the name Jenny, often seen as a feminine representation, tends to be transliterated as 珍妮. The selected hanzi mean treasure and girl separately, occurring with an enchanting imagery to natives; it takes a monster to transliterate such a lovely name into 真泥. While phonetically identical, it conjures a REALLY MUDDY visual resonance. In title localization, sound symbolism governs how Chinese localizers choose hanzi for their sound-based strategy. That’s right – Chinese transliteration can be seen as a management of the superficial phonetic property and the hidden semantic relations of each hanzi.

A notorious case is Nintendo’s turf-war game Splatoon. Chinese fans rolled their eyes to the moon when seeing its official name 斯普拉遁 for the first time. Admittedly, the pronunciation is faithful, but the only meaningful hanzi is the last one, 遁, featuring Splatoon’s hide-and-swim gameplay. As for the other three, well, they act like awkward fillers that fail to cohere into a valid combination. The name delivers no cognitive sonance. Forced transliterations, especially among products from Japan, are presumably required by the IP owner. Doraemon, once widely known as 机器猫 ‘Bot Cat’ or 小叮当 ‘Little Jingle’ back in the 80s, was changed to 哆啦A梦, ‘Do La A Dream’ in the 90s by honoring the author Fujiko F. Fujio’s will. Despite this intention to unify the brand across East Asian markets, the transliteration felt alien to Chinese audiences. Even today, it is not hard to find advocates who still prefer old, meaningful names. Another case is Pokémon. The franchise’s vintage names, such as 宠物小精灵 ‘Pet Fairies’, 口袋妖怪 ‘Pocket Monsters’, and 神奇宝贝 ‘Wonderous Pets’, while swept under the rug, still win many hearts because of their evocative clarity.

Ignoring native naming patterns is a recipe for rejection. Transliteration is a great choice in certain cases, but in game title localization, its application demands scrutiny, as the potential for backlash often outweighs its advantages. That’s why the aforementioned names, 哆啦A梦, 斯普拉遁, and 宝可梦 have been bashed by Chinese fans for years. While the employment of sound adaptation has been widespread in Japan after the Meiji period and introduced numerous foreign concepts to the Land of the Rising Sun, such forced transliteration strategies, however common in Japan, still face resistance in Chinese markets.

NARRATIVE-BASED

Localization strategies exist along a spectrum, often overlapping and blending. A sound-based localization can also be a transference one; a word-for-word localization may introduce words that might be argued as synonyms. Similarly, the narrative-based localization stays close to transcreation, yet the former doesn’t necessarily erase the original information from SL texts. On the contrary, narrative-based localization lays an extra stroke in texts, augmenting contextual layers with the initial title, especially when a title is overly succinct. One of many plausible gateways to inject more information is the narrative, and occasionally the gameplay.

The Ascent, a solo and co-op Action-shooter RPG by Neon Giant, didn’t reveal much in its English title. Hardly can we know what the game is about without scrolling down its Steam page. Plain titles like this challenge localizers, forcing them to look beyond the title itself – to the game’s narrative, setting, and mechanics – before reconstructing a more informative translation. What information should we add, and what information should we cull? Eventually, a to-the-point title for The Ascent in Chinese is presented: 上行战场, ‘The Ascent Battlefield’. Set in a dystopian arcology where syndicates and rival corporations wage violent territorial wars, the addition of ‘battlefield’ captures the game’s core loop of combat-heavy action while maintaining the upward trajectory implied by ‘ascent.’

The Ascent is not the only narrative-based case you can find in localization history. Journey, the award-winning game by Thatgamecompany, also applied the same approach to localize its Chinese title. In this indie adventure game, players control a robed figure traveling through a vast desert towards a distant mountain. The emphasis on emotional experiences and companionship in silence impressed everyone. When traditional communications between players are stripped away, the game evokes a sense of uncertainty in a vast world of anonymous figures. Every relationship is ephemeral, and the only way to progress in the game is to depart from your old friends. No wonder the Chinese localizer(s) chose 风之旅人 as its official name. Travelers of the Wind. What a name.

Narrative-based localization retains the core concept while clarifying its context, often making the title more informative. The core concept being preserved can derive from either a keyword in the source title or a gameplay feature – the source doesn’t matter. When gameplay features are more distinctive than the title itself, localizers may prioritize game content over textual fidelity. Such content-driven rewriting remains a form of narrative-based localization. Meet It Takes Two, a 2021 cooperative platformer game developed by Hazelight Studios. The Chinese name, 双人成行, ‘Two Journey Together’, beautifully features the cooperative essence. While the English title is an omitted idiom and creates a gentle pause in sound and a lingering imagination in visuals, the Chinese rebirth, based on its core gameplay, reveals the game’s mandatory two-player cooperation. This localized name outlines embarking together. Moreover, as you already know, Chinese words have their inbuilt syntax resonance. The word choice 双人 easily navigates to synonyms or collocations such as 双双, 双全, 成双作对, 两人世界, etc, mostly connoting a happy conjugal partnership. Amazing enough, the romantic constituent ‘to tango’ omitted in English found another way to reappear in the Chinese semantic network. What is lost in translation is found back in its subtexts.

References

Richard Moss, Assassin’s Creed: An oral history

Vlad Mazanko, Hades Originally Featured Theseus As A Protagonist To Escape The Labyrinth

AsgoreD. 好评如潮的《冲就完事模拟器》,今日结束抢先体验正式发售

上海人民出版社. 太平军在上海——《北华捷报》选译

What’s the meaning of the title for the “Far Cry” video game series?

Robert Zak, How Crytek became one of the biggest names in PC gaming

Wade Steel, Ubisoft Acquires Rights to Far Cry

尹口羊Erfolg. 将《Far Cry》系列翻译成《孤岛惊魂》是很有问题的

Peter Newmark, About Translation.

Luke Plunkett, Why Was “Biohazard” Changed To “Resident Evil”?

木木的世界线. 生化危机VS恶灵古堡:一个游戏为什么有两个名字?Resident Evil/Biohazard命名内幕:商业妥协还是文化包装?背后的真相揭秘!

小魚兒諸葛亮. 「惡靈古堡」是一個好譯名!

达观数据. 用文本挖掘剖析54万首诗歌,发现了这些

James Lucas, I Miss Ratchet & Clank’s Tongue In Cheek Naming

编剧雷神OFFICIAL. 俄罗斯方块为什么叫这名 | Why does Tetris called Tetris?

Steven Chung, ‘Tetris’: A Simple Game With A Complex Cold War Past

游戏观察. 抢注商标让《海贼王》版权方集英社无法维权

Daisy ZONG, Analysis on Pros and Cons of Madrid Trademark Registration – From the Perspective of Obtaining Protection for Foreign Trademarks in China

Michael Kondoudis, How to Trademark a Game: The ULTIMATE Guide

Monika Wieczorkowska, Lena Marcinoska-Boulangé, The name of the game: Video game titles and trademark protection

北京中周法律应用研究院, 北京-长三角知识产权保护实务智库, 南京大学紫金知识产权研究中心.《游戏商标保护白皮书》

Said Shiyab, Synonymy in Translation

胡波,张璘. 儿童文学翻译中的创造性叛逆——赵译《阿丽斯漫游奇境记》研究

游民星空官方, 官方在起中文名时,为啥总那么沙雕?

About the Author

George Ou is a localizer. He serves gamers with his words in print and digital. His deliveries have been read in over 200 popular culture publications.